Tilapia

Oreochromis / Sarotherodon / Tilapia spp.

Sources, Quantities and Cultivation Methods

Sources and Quantities

Tilapia is the common name given to the 112 freshwater and brackish water fish species and subspecies of three genera: Oreochromis (maternal mouthbrooders), Sarotherodon (paternal mouthbrooders), and Tilapia (substrate spawners), native to the tropical and subtropical regions of Africa and the Middle East1. Naturally they occupy a wide range of usually freshwater habitats such as rivers, lakes and irrigation channels, but depending on the species, would be able to tolerate different levels of salinity. Tilapia are omnivorous and can feed on a variety of items, including diets containing a high proportion of plant material.The UK fish labelling regulations2 designate that all products of the genera Oreochromis and Tilapia can be labelled ‘tilapia’.

Whilst wild capture is relatively small, several species of tilapia are cultured commercially on a large scale. By far the most dominant farmed tilapia species is the Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus)3, accounting for more than 70% of the total production in 2018, with various hybrids between this and other species also significant in aquaculture4.

Tilapia can be farmed in different types of systems and within a wide range of densities. Termed the “aquatic chicken”, because of their relative ease of culture, rapid growth and palatability, tilapias are some of the most important aquaculture species globally. They are second only to carps in terms of volume and produced in more nations than any other farmed food fish5.

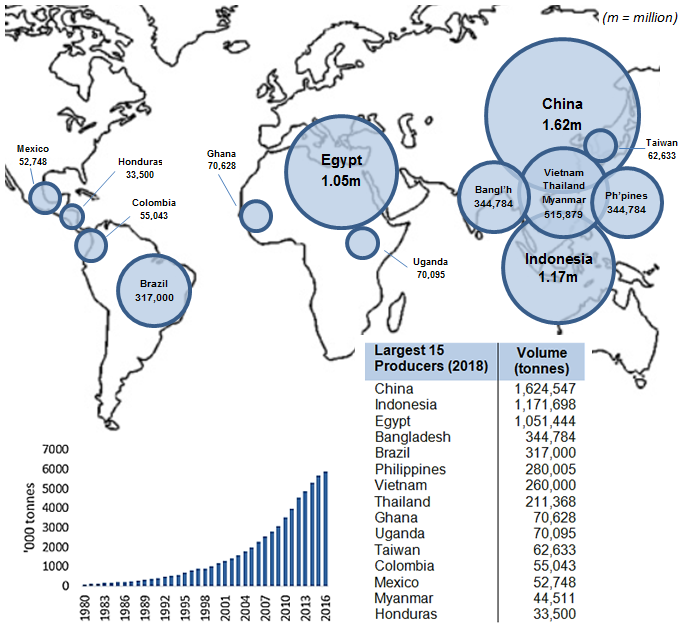

Global production of tilapia has increased from around 1 million tonnes in 2000 to 5.97 million tonnes in 2018, valued at almost US$11.2 billion. Of the 120+ nations reporting tilapia production worldwide, China alone accounted for 27% of the 2018 global volume. The three largest producers - China, Indonesia and Egypt - accounted for 64% of 2018 production4.

The European market for tilapia is still relatively small but growing. In 2014 the EU-28 imported 7,500 tonnes of frozen fillets and 5,812 tonnes of whole frozen tilapia, almost entirely from Asian countries. China was the leading supplier (68%) followed by Viet Nam (17%), Indonesia (6.7%) and Thailand (5.8%). A new market supplier is Myanmar6.

Today almost no tilapia is farmed in Europe due to lack of demand and production costs (e.g. heating water in recirculation systems). Historically most tilapia production in Europe took place in the Netherlands and Belgium, with the first farms operational in the early 1980’s. There have been many attempts and failures in Europe to develop the industry; the UK has seen tilapia aquaculture initiatives develop since the early 2000s, but few have survived. The only remaining domestic producers are a handful of small, often aquaponic systems.

Domestic Market Information

Our domestic seafood market is complex mix of products from wild caught and farmed species, including tilapia.

To discover more about the highly dynamic and ever-changing UK and Great British (GB) seafood marketplace, you can explore our user friendly and interactive Trade and Tariff in Tableau (T4) online tool. And visiting our dedicated Insight and Research pages will provide you with access to a wealth of information, from reports to factsheets on markets including:

- Retail – data from independent and multiple retailers in the UK used to reveal the latest insights on seafood eaten at home

- Foodservice – data from the foodservice industry in the UK used to highlight the latest trends on seafood eaten out of home

- Market supply – HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) data used to detail what species and products are imported from, and exported to, the UK

To get the latest seafood market performance and trends delivered to your inbox, register at the Market Insight Portal.

Production Method

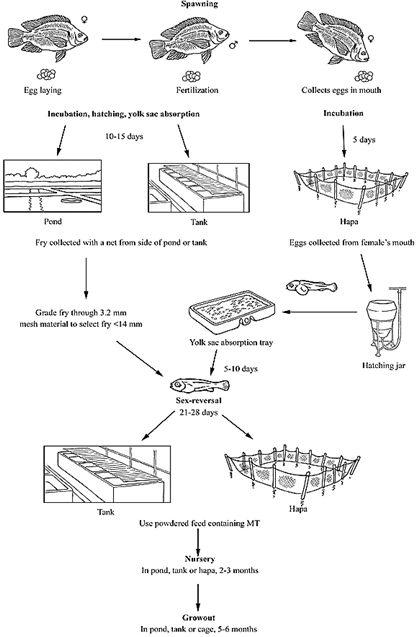

The most common commercially produced tilapia species, the Nile tilapia, are prolific breeders and as long as their physiological requirements are met, spawning can occur year-round. Farm broodstock are often placed in ponds, tanks or hapas (net enclosures in ponds) where they would spawn naturally and the offspring (mixed-sex) can be subsequently stocked into grow-out facilities.

On average, it takes 6-12 months to grow a market-sized tilapia of 200-600g. However, the presence of female tilapia in the grow-out phase is undesired because females begin reproducing as early as 6 months after hatching and thus divert their food energy from growth to reproduction. Moreover, uncontrolled reproduction, typically in earthen ponds, results in excessive recruitment of fingerlings, competition for food and stunting of the original stock, which results in a harvest containing fish with a wide range of sizes and weights. As fillet weight and yield are the main traits of economic interest for most commercial tilapia producers, several methods have been developed for the production of all-male (mono-sex) tilapia fingerlings3.

The ‘simplest’ but most labour-intensive method is the manual selection of males, which is rarely used nowadays. The two most common techniques in commercial tilapia aquaculture are hybridization and sex-reversal. Hybridisation, or the crossing of two different species, is relatively easy with tilapias and can results in the production of predominantly male offspring with the desired growth and production characteristics7 but is not a reliable technique and now little used. The hybridization between Nile tilapia and Blue or Mozambique tilapia is a relatively common practice.

Alternatively, in order to reverse the sex of female Nile tilapia to phenotypic male, swim-up fry (generally <9mm in length) may receive a male sex hormone (17-α-Methyltestosterone, also abbreviated to ‘MT’) in feed for a period of 3-4 weeks3. Manual collection of eggs from the female’s mouth, also known as “egg robbing”, is by far the most efficient way to produce synchronised batches of swim-up fry for MT treatment. It is important to begin treatment at swim-up, since the first week is the most critical for achieving a high percentage of masculinization. While MT treatment does not pose risks to consumers as there is no accumulation of the hormone in fish flesh and it quickly reaches normal levels after cessation of treatment8, the use of hormones and growth promoters in animals destined for the human food chain is banned under EU Directive 81/602/EEC.

There has been a lot of effort to improved stocks in order to increase the productivity of tilapia aquaculture. The main strain that is now used in many producer countries is the so-called GIFT strain (Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia) - the outcome of Filipino research in the 1990s9, and various breeding programmes are still on-going using GIFT tilapia.

The GIFT strain grows much faster in cultured conditions than other strains of tilapia, significantly reducing the time it takes to grow the fish to market size with reports of body weights up to 58% higher than ‘non-GIFT’ strains on ‘average’ farms in Asia. This greatly increases the profitability of such operations.

Tilapia are cultivated in a wide range of systems including earthen ponds, freshwater net-pens, raceways and high-tech re-circulating aquaculture systems (RAS)3, 10-12. The choice of system depends on available resources, environmental conditions (especially climate), socio-economic factors, technology and marketing potential.

Pond Culture

Ponds are versatile and cost-effective systems for extensive, semi-intensive and intensive tilapia production. Part of the fish nutrition is usually provided by naturally occurring food, such as phyto- and zoo-plankton, stimulated to develop by fertilizing the ponds. It is only viable in tropical and sub-tropical environments where temperatures are high and stable year-round and sufficient land and water quantities are available.

Net-Pen or Cage Culture

Net-pens for tilapia culture can be placed in tropical and subtropical water bodies such as lakes, reservoirs, rivers and irrigation systems. Compared to ponds and raceways, the use of cages requires relatively low capital investment and offers flexible management. Another advantage is that the breeding cycle of tilapia is disrupted in cages, and therefore mixed sex population can be reared without the problems of producing large quantities of small fish, which are major constraints in pond culture.

Raceways, Tanks and RAS

Flow-through raceways / tanks and re-circulating aquaculture systems (RAS) are land-based and can be a good alternative to pond or cage culture if sufficient water or land is not available and the economics are favourable9. Unlike in ponds, it is easier to manage the stock, exert a high degree of environmental control through appropriate water treatment systems, prevent pollution, and escapes (especially in RAS). However, these methods require much higher investments and there have been a number of business failures13.

References

- FishBase

- UK DEFRA

- FAO

- FAO FishstatJ

- Rabobank

- TheFishSite

- Rahman M.A., Arshad, A., Marimuthu, K., Ara, R., Amin, S.M.N. 2013. Inter-specific Hybridization and Its Potential for Aquaculture of Fin Fishes. Asian Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances, 8: p139-153

- Megbowon I. and Mojekwu, T.O, 2014. Tilapia Sex Reversal Using Methyl Testosterone (MT) and its Effect on Fish, Man and Environment. Biotechnology, 13, p213-216.

- Ansah, Y.B., Frimpong E.A., Hallerman E.M. 2014. Genetically-Improved Tilapia Strains in Africa: Potential Benefits and Negative Impacts. Sustainability, 6(6), p3697-3721

- Seafood Watch

- Seafood Watch

- Seafood Watch

- HIE