Rainbow Trout

Oncorhynchus mykiss

Feed

Fish Meal and Fish Oil

Marine ingredients such as Fishmeal (FM) and Fish Oil (FO) provide nutrients that often cannot be found in other feed materials (e.g. particular amino acids, vitamins and minerals), and they are essential constituents of many aquafeeds. FM and FO are a finite resource and are seen by the aquaculture industry as a strategic ingredient to be used efficiently and replaced where possible1.

Indeed, the ratio of wild fish input (via feed) to total farmed fish output fell by more than one third between 1995 and 20072. A continuing decrease in FM and FO inclusion in aquafeeds is predicted as feed companies develop formulations which increasingly reduce these marine ingredients.

Globally the FM and FO used in aquafeeds is increasingly derived from fishery and aquaculture processing by-product; the utilisation of these by-products as a raw material for FM and FO production is in the region of 25%-35% and this trend will continue; it is expected to rise to 49% by 20221, 3, 4.

IFFO The Marine Ingredients Organisation5 (formerly known as The International Fishmeal and Fish Oil Organisation or IFFO) estimate that if aquaculture is taken as a whole, producing one tonne of fed farmed fish (excluding filter feeding species) now takes 0.22 tonnes of whole wild fish. This essentially means that for every 0.22 kg of whole wild fish used in FM production, a kilo of farmed fish is produced; in other words, for every 1 kg of wild fish used 4.5 kg of farmed fish is produced6.

Perhaps the most important mitigation measure is to ensure that products such as FM and FO used to manufacture aquafeed come from legal, reported and regulated fisheries. Such fishery products can demonstrate their sourcing adheres to the United Nation Food and Agriculture Organisation (UN FAO) “Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries”7, known as CCRF, through several mechanisms:

- The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC)8 which certifies fisheries to an international standard based on FAO best-practice requirements

- IFFO RS Global Standard for Responsible Supply (IFFO RS)9 which certifies FM and FO through a process which includes the assessment of source fisheries against a set of CCRF-based requirements

- Information platforms such as FishSource10 or FisheryProgress11 which provide information and analysis without a certification or approval rating

Currently around 1.9 million tonnes of FM production is certified as either IFFO RS or MSC – representing about 40% of global production; most of this comes from South America, but Europe and North America are providing significant volumes, and North Africa currently has certified production. Currently there is no certified FM product produced in China and only very small quantities (less than 10,000 tonnes) are produced in the rest of Asia (and this is from by-products). Given that Asia produces around 1.5 million tonnes of FM, there is obviously considerable room for improvement, in both fisheries management and certification uptake12.

Aquaculture certification schemes also require that fish products used in feeds are not on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red lists13 of threatened species or the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)14 lists of endangered species.

GM Feed Ingredients

The use of genetically modified (GM) vegetable ingredients in animal feedstuffs (including aquafeed) is an ongoing area of debate15. Whilst some contend that GM soy can help support current levels of aquaculture, global attitudes and consumer perceptions about the use of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) vary in different parts of the world, with North American markets being far less averse than European ones. However, their use in all livestock feed is widespread, and in the EU food from animals fed on authorised GM crops is considered to be as safe as food from animals fed on non-GM crops16.

Rainbow trout Feed

Careful management of food and feeding regimes are important to the success of rainbow trout aquaculture. To reduce wasting aquafeed on farms, efficient feed use can be monitored and should comply with levels set in certification standards. The indicators used can include the Feed Conversion Rate or FCR (the amount of feed an animal requires to gain a kilogram of body weight), economic feed conversion ratio (eFCR), maximum fish feed equivalence ratio (FFER), or protein efficiency ratio (PER).

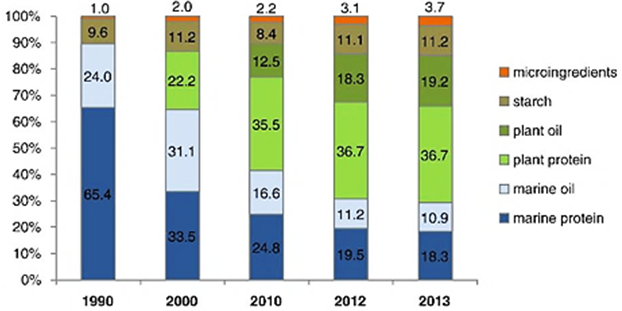

Rainbow trout, like Atlantic salmon, have a requirement for a high protein diet and whilst their aquafeeds are still relatively high in FM and FO, vegetable materials are increasingly substituting these marine ingredients. The graph shows that in 1990 90% of the ingredients in Norwegian salmon feed were of marine origin, whereas in 2013 it was only around 30%17, and this trend is set to continue for a number of farmed species including trout18.

Trout farming around the world has historically seen FCRs ranging from 0.7 to 2.0 with a global average of 1.2519. More recent figures indicate FCRs for trout farmed in flow-through ponds around 1.1620 and 1.3-1.6 for trout farmed in freshwater21 and marine22 net-pens. Lower FCRs have been achieved in land-based trout farms in Denmark where according to the Danish environmental legislations, FCR must not exceed 1.023.

FCR improvements in salmonid feeds has reduced feed requirement per tonne of salmonids produced by around 60% since the 1980s24. IFFO The Marine Ingredients Organisation estimate that in 2015 for every 0.83 kg of whole wild fish used in FM production for all salmonids (i.e. salmon and trout) aquafeeds, a kilo of farmed salmonids was produced. This means that the salmonid feed industry supports the production of more farmed fish than it uses as feed fish, which appears to be the first time this has been recorded6. As feed companies constantly develop their aquafeed formulations the decreasing inclusion of marine ingredients will continue.

Flesh Pigments

The pink colour of salmon and trout flesh, whether wild or farmed, results from the retention of carotenoids in the fish flesh. Astaxanthin is a naturally occurring carotenoid pigment25 found in wild salmon and crustaceans. Trout (and salmon) cannot make their own astaxanthin; they consume it in their diet. The diet of wild fish includes krill, zooplankton, small fish and crustaceans all of which naturally contain astaxanthin. There are several health benefits from astaxanthin for salmonids; it is a potent antioxidant and a source of vitamin A and helps to protect tissues, stimulate the immune system and improve fertility and growth26. In order to confer these health benefits to farmed rainbow trout, as well as to recreate the pink flesh colour of wild fish27, astaxanthin (either natural or synthetic) is introduced into their pelletised feed during the grow-out phase.

There is no difference between the natural and synthetic forms of astaxanthin; both are processed and absorbed by wild and farmed fish in exactly the same manner26, 28. Both natural and synthetic forms are considered safe for use in trout diets, and their use up to the maximum permitted dietary level for trout is of no concern for consumer safety16, 29. Seafood buyers often use colour charts such as a ‘Salmofan’30 to compare different salmon flesh colour, and whether the pigment used is natural astaxanthin (extracted from crustacean shell, Phaffia yeast31, or predominately from the bacteria Paracoccus carotinifaciens producing the pigment Panaferd32 or synthesized, depends on the requirements of the particular brand or retailer.

References

- IFFO

- Naylor, R.L., et al, 2009. Feeding aquaculture in an era of finite resources. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (36), pp15103-15110

- FSA

- IFFO

- IFFO

- IFFO

- FAO

- MSC

- IFFO RS

- FishSource

- FisheryProgress

- IFFO

- IUCN

- CITES

- Sissener, N.H. et al, 2011. Genetically modified plants as fish feed ingredients. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 68(3), p563-574

- FSA

- Ytrestøyl, T., Aas, T.S., and Åsgård, T., 2015. Utilisation of feed resources in production of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in Norway. Aquaculture. 448, pp365–374

- IFFO (pers. comm.)

- Tacon, A. G. J. & Metian, M., 2008. Global overview on the use of fish meal and fish oil in industrially compounded aquafeeds: Trends and future prospects. Aquaculture, 285: 146-158

- MBA

- MBA

- MBA

- Jokumsen and Svendsen 2010. Farming of Freshwater rainbow trout in Denmark

- Little, D. and Shepherd, C.J., 2014. Aquaculture: are the criticisms justified? II – Aquaculture’s environmental impact and use of resources, with special reference to farming Atlantic salmon

- Mahfuzur R., Shah, M.R., Liang, Y., Cheng, J.J. and Daroch, M., 2016. Astaxanthin-Producing Green Microalga Haematococcus pluvialis: From Single Cell to High Value Commercial Products. Frontiers in Plant Science. 7

- Skretting

- FAO

- NOAA

- European Food Safety Agency

- DSM

- Sanderson, G.W. and Jolly, S.O., 1994. The value of Phaffia yeast as a feed ingredient for salmonid fish. Aquaculture. 124(1–4), pp193-200

- JXTG Group