Atlantic Halibut

Hippoglossus hippoglossus

Sources, Quantities and Cultivation Methods

Sources and Quantities

Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) is a large, slow growing flatfish species in the family Pleuronectidae, maturing around 10-14 years. In the wild they can reach over 300kg and be 4.7m long1. Halibut are distributed throughout the north Atlantic in cold waters (typically 5-8°C), and includes the waters off the Norway coast, Faroes, Iceland and southern Greenland, although they can be encountered as far south as Maine in North America, and the Bay of Biscay.

The production of Atlantic halibut from capture fisheries has been steadily declining in the last century, reaching its lowest point in 1998 of only 3,346 tonnes2. In 1996 it has been classified as ‘endangered’ by the IUCN3.

Due to the limited supply from the wild and strong market demand, there have been efforts to farm Atlantic halibut since the 1980s in Norway, Scotland, Iceland and Canada4. However, its protracted early life stages meant problems with poor survival rates and fry quality which have restricted the industry's development5.

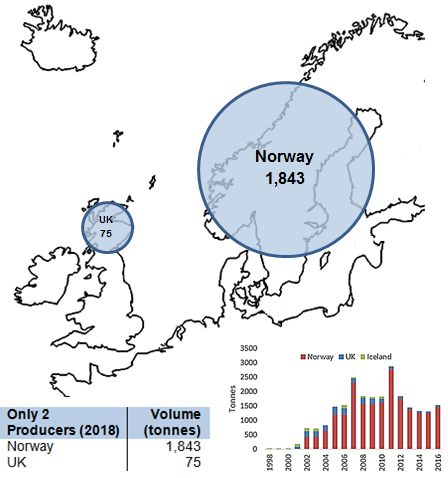

Global aquaculture production of Atlantic halibut remains small, peaking at 2,883 tonnes in 2011. It has since decreased and in 2018 1,918 tonnes was produced worth some US$2.3 million. Norway accounted for 96% of this production, with the remainder coming from Scotland2, 6.

Domestic Market Information7, 8

Over the past ten years, halibut has been in steep decline in Great British retail (i.e. in England, Scotland and Wales), with value down -77% and volume down -85% respectively from a base of £4.8 million and 182 tonnes in 2008. Halibut sales have undoubtedly been hit by austerity as it has one of the highest average prices, almost double that of scallop.

In 2018, UK retail sales of halibut were worth £1.15 million (-2.7% compared to the previous year) with a volume of 27 tonnes (-4.5%), average price £40.98 per kg (+1.9%); ranking as the 40th most popular species by value in the 52 weeks up to 16/06/2018 (including discounters).

In 2018, the UK imported 1,113 tonnes of halibut.

Note: the difference between volume of Atlantic halibut sold in UK retail and that which is imported is due to its use in the foodservice industry (e.g. restaurants) (no data available) and that which is re-exported.

Production Method1, 10

The halibut has a complex lifecycle. Sexually mature females produce several separate batches of eggs each season. In the wild, Atlantic halibut spawn in winter and early spring but in captivity they can be induced to spawn all year round by controlling the day length (photo-period); possible as broodstock are typically held in large indoor tanks.

Broodstock are stripped by hand and the eggs and milt mixed. The fertilized eggs are then held in upwelling conical incubators of 70-500L capacity at 4-6°C until they are ready to hatch (approximately 14 days). Dead eggs are removed using bottom flushing systems. Shortly before hatching, viable eggs are transferred into large static, or gently upwelling, ‘yolk-sac’ incubators. These can be greater than 10m3 and house the yolk-sac larvae for more than 45 days after hatching at constant temperature of 5.5-6.0°C. This period is the most critical for halibut operators as the larvae are reliant on their yolk for food, while being very fragile and vulnerable to microbial infection or physical damage. Towards the end of the yolk-sac stage, the larvae are fed small live crustaceans; marine copepods or Artemia (the latter enriched with essential fatty acids e.g. DHA and EPA).

The developing larvae go through a metamorphosis where they transform to a flatfish shape, and their transparent skin becomes pigmented. The body transformation requires one of the eyes to move around the head so both eyes are on the same side. The juvenile fish then use their other side of the body to lie on the substratum (e.g. tank floor). Halibut larvae are nutritionally very demanding. If fed an unsuitable diet, they will undergo an incomplete metamorphosis (the eyes will not properly rotate) and they may not pigment properly. Once the halibut becomes a juvenile, rearing is relatively straightforward if husbandry needs are met. Additional surface area is provided for them to lie on, and feed must be presented to elicit a feeding response. There can be aggression issues at the juvenile stage that can result in eye losses, although these can usually be controlled through manipulation of feeding and light regimes.

The grow-out phase of Atlantic halibut can take place in both land-based tanks and in flat-bottomed floating marine net-pens (sea cages). The land-based systems can be pump-ashore systems (PAS) where new sea water constantly ‘flows-through’ the farm; or involve recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) where sea water is purified and recycled.

When grown-out in marine net-pens, a further on-shore “nursery phase” is needed to on-grow hatchery juveniles of 5-10g to “cage-ready” juveniles of more than 100g.

Halibut tend to feed and grow well at temperatures ranging from 8 to 15° C. In areas where these temperatures are maintained for most of the year, halibut can reach a market size of 3-4 kg after 24-27 months at sea. Female halibut grow faster than males, and for this reason some producers are now reportedly rearing all female stocks. The typical time taken from egg to a harvest weight of 5kg is about four years. Much of the northern UK coastline has a suitable temperature profile for halibut aquaculture and thus presents a good opportunity for further development of the industry.

References

- Diversify Project

- FAO FishstatJ

- Sobel, J. 1996. Hippoglossus hippoglossus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Diversify Project

- Diversify Project

- Gigha Halibut

- AC Nielson

- HMRC

- Seafish

- Haug, T. 1990. Biology of the Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus (L. 1758). Advances in Marine Biology 26, 1-70